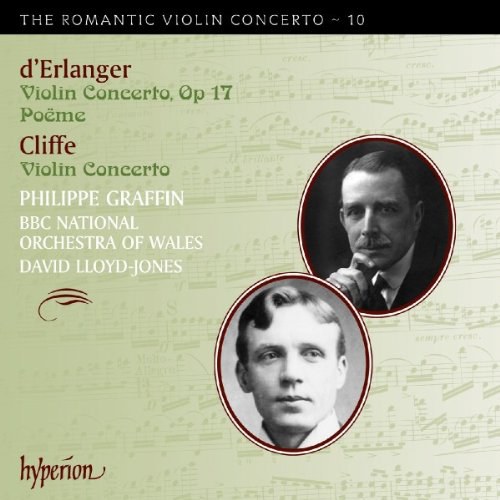

德·厄兰格:小提琴协奏曲/音诗;克利夫:小提琴协奏曲 豆瓣

Philippe Graffin

/

BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra

…

类型:

古典

发布日期 2010年4月1日

出版发行:

Hyperion

BARON Frédéric Alfred d’Erlanger was a banker,

born in Paris but with a German father and

American mother, who moved to London in his

teens. He was naturalized British and long resident in

London, where he was involved in promoting music and

was later a trustee of the London Philharmonic Orchestra

and on the board of the Royal Opera House, Covent

Garden. He was also a composer, his teacher being Anselm

Ehmant, a close friend of the family, and although his

catalogue of works is not huge, throughout his life there

was a steady stream of first performances bythe most

celebrated artists and orchestras of the day. Many record

collectors will have come across him as the composer of

the ballet music Les cent baisers, recorded by Dorati and

the London Symphony Orchestra after its success when

danced at Covent Garden in 1935.

D’Erlanger had first appeared as a composer with his

opéra comique Jehan de Saintré, produced in Aix-les-

Bains in 1893 and in Hamburg the following year. He first

appeared at Covent Garden as a stage composer in July

1897, under the pseudonym Frédéric Regnal, with the

opera Inès Mendo after Mérimée’s comedy. Later, with

theGerman title Das Erbe, it was produced in Hamburg,

Frankfurt and Moscow.

If we track his music through his published works,

andlater through performances at the Queen’s Hall

Promenade Concerts, we find a Prelude for violin and

piano published in 1895 and an album of six songs in

1896. He appeared at the Proms in September 1895 with

a Suite symphonique, and by 1900 had published a Violin

Sonata in G minor and in 1901 a notable Piano Quintet,

which was given a rousing reception at the 1902 ‘Pops’ at

St James’s Hall. New works appeared at regular intervals

during his life: just following the Proms we find the

Andante symphonique Op 18 for cello and orchestra in

October 1904, and the symphonic prelude Sursum Corda!

in August 1919. There was also the Concerto symphonique

for piano and orchestra from 1921 and the gorgeous

Messe de Requiem of 1930, a work admired by Adrian

Boult, who arranged its broadcast in 1931 and a public

performance in Birmingham in 1933, where it was revived

as recently as March 2001. The briefly popular orchestral

waltz Midnight Rose was recorded by Barbirolli in 1934.

Possibly d’Erlanger’s most famous work was his opera,

in Italian, after Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

Someone with d’Erlanger’s connections would only con-

sider the best as his collaborators and he asked Luigi Illica,

Puccini’s librettist, to write the libretto. Its first production

at the San Carlo Theatre in Naples in 1906 was interrupted

by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The Naples

production spawned early recordings by Amedeo Bassi and

Alessandro Bonci of Angel Clare’s aria in Act I. Produced

inLondon in 1909 with no less a cast than Emmy Destin

as Tess and Zenatello as Angel Clare, it was revived in 1910

and later produced at Chemnitz and Budapest. Tess was

revived by the BBC in 1929 in an English version. In 1910

his opera Noël was produced atthe Paris Opéra and

subsequently in Chicago, Philadelphia, Montreal and

Stockholm.

So d’Erlanger’s Violin Concerto was the work of a

significant emerging composer when it was written in

1902. It was first performed by Hugo Heermann, then still

the long-standing professor of violin at the Hoch’sche

Konservatorium in Frankfurt, and he played it in Holland

and Germany before it was taken up by Fritz Kreisler and

given its British premiere at the Philharmonic Society

concert at Queen’s Hall on 12 March 1903. Published

byRahter of Hamburg in 1903, it was later played at

Bournemouth in 1909, 1920 and 1928, as well as at the

Queen’s Hall Proms (by Albert Sammons) in 1921.

Notable for the transparency of its scoring, d’Erlanger’s

concerto launches straight into the first subject, an-nounced by the soloist in triple- and double-stopped

chords without an orchestral introduction. The soloist

soars away in running semiquavers, eventually presenting

a more lyrical version of the theme and immediately

moving on to the singing second subject. A succession

ofrising trills by the soloist leads to a cadenza-like

unaccompanied middle-section before the first subject

reappears in the orchestra. The lyrical second subject

returns in various keys and with a short coda, Allegro

animando, the horns herald the close and a brief gesture

of dismissal.

The composer’s treatment of the orchestra—with

constantly varied touches of instrumental colour, and

often with only two or three instruments playing, typically

answering each other—is particularly characteristic in the

gorgeous slow movement. A nine-bar introduction creates

a nocturnal atmosphere with bell-like notes on flute and

harp over hushed strings. The cor anglais then sings the

plaintive first subject, immediately repeated and extended

by the soloist. After thirty-one bars it is taken up by the

clarinet, the soloist now accompanying with arpeggiated

chords across the strings. The second subject follows on

the strings with rising decorations by the soloist. The first

theme is repeated, now in F minor, with muted accom-

panying strings. A haunting romantic motif is heard on the

horns and will be heard several times before the end.

Eventually a cadenza-like passage of running semiquavers

presages the return of the cor anglais and a brief

orchestral climax before, musing on the horn’s romantic

motif, the music fades on the soloist’s long-held pianis-

simo top C.

The finale comes as a great surprise—a diaphanous

scherzando, all fairy gossamer. The music falls into a

succession of sixteen related short episodes. The first

theme starts in

and proceeds in

, its leaping triplet

motion giving it the feel of a saltarello. A contrasted theme in

appears in the strings in the fifth episode, and in the

next the first theme of the first movement returns in

staccato crochets. The writing for the soloist is brilliant

throughout, though d’Erlanger does not feel the need for

another cadenza.

born in Paris but with a German father and

American mother, who moved to London in his

teens. He was naturalized British and long resident in

London, where he was involved in promoting music and

was later a trustee of the London Philharmonic Orchestra

and on the board of the Royal Opera House, Covent

Garden. He was also a composer, his teacher being Anselm

Ehmant, a close friend of the family, and although his

catalogue of works is not huge, throughout his life there

was a steady stream of first performances bythe most

celebrated artists and orchestras of the day. Many record

collectors will have come across him as the composer of

the ballet music Les cent baisers, recorded by Dorati and

the London Symphony Orchestra after its success when

danced at Covent Garden in 1935.

D’Erlanger had first appeared as a composer with his

opéra comique Jehan de Saintré, produced in Aix-les-

Bains in 1893 and in Hamburg the following year. He first

appeared at Covent Garden as a stage composer in July

1897, under the pseudonym Frédéric Regnal, with the

opera Inès Mendo after Mérimée’s comedy. Later, with

theGerman title Das Erbe, it was produced in Hamburg,

Frankfurt and Moscow.

If we track his music through his published works,

andlater through performances at the Queen’s Hall

Promenade Concerts, we find a Prelude for violin and

piano published in 1895 and an album of six songs in

1896. He appeared at the Proms in September 1895 with

a Suite symphonique, and by 1900 had published a Violin

Sonata in G minor and in 1901 a notable Piano Quintet,

which was given a rousing reception at the 1902 ‘Pops’ at

St James’s Hall. New works appeared at regular intervals

during his life: just following the Proms we find the

Andante symphonique Op 18 for cello and orchestra in

October 1904, and the symphonic prelude Sursum Corda!

in August 1919. There was also the Concerto symphonique

for piano and orchestra from 1921 and the gorgeous

Messe de Requiem of 1930, a work admired by Adrian

Boult, who arranged its broadcast in 1931 and a public

performance in Birmingham in 1933, where it was revived

as recently as March 2001. The briefly popular orchestral

waltz Midnight Rose was recorded by Barbirolli in 1934.

Possibly d’Erlanger’s most famous work was his opera,

in Italian, after Thomas Hardy’s Tess of the d’Urbervilles.

Someone with d’Erlanger’s connections would only con-

sider the best as his collaborators and he asked Luigi Illica,

Puccini’s librettist, to write the libretto. Its first production

at the San Carlo Theatre in Naples in 1906 was interrupted

by a volcanic eruption of Mount Vesuvius. The Naples

production spawned early recordings by Amedeo Bassi and

Alessandro Bonci of Angel Clare’s aria in Act I. Produced

inLondon in 1909 with no less a cast than Emmy Destin

as Tess and Zenatello as Angel Clare, it was revived in 1910

and later produced at Chemnitz and Budapest. Tess was

revived by the BBC in 1929 in an English version. In 1910

his opera Noël was produced atthe Paris Opéra and

subsequently in Chicago, Philadelphia, Montreal and

Stockholm.

So d’Erlanger’s Violin Concerto was the work of a

significant emerging composer when it was written in

1902. It was first performed by Hugo Heermann, then still

the long-standing professor of violin at the Hoch’sche

Konservatorium in Frankfurt, and he played it in Holland

and Germany before it was taken up by Fritz Kreisler and

given its British premiere at the Philharmonic Society

concert at Queen’s Hall on 12 March 1903. Published

byRahter of Hamburg in 1903, it was later played at

Bournemouth in 1909, 1920 and 1928, as well as at the

Queen’s Hall Proms (by Albert Sammons) in 1921.

Notable for the transparency of its scoring, d’Erlanger’s

concerto launches straight into the first subject, an-nounced by the soloist in triple- and double-stopped

chords without an orchestral introduction. The soloist

soars away in running semiquavers, eventually presenting

a more lyrical version of the theme and immediately

moving on to the singing second subject. A succession

ofrising trills by the soloist leads to a cadenza-like

unaccompanied middle-section before the first subject

reappears in the orchestra. The lyrical second subject

returns in various keys and with a short coda, Allegro

animando, the horns herald the close and a brief gesture

of dismissal.

The composer’s treatment of the orchestra—with

constantly varied touches of instrumental colour, and

often with only two or three instruments playing, typically

answering each other—is particularly characteristic in the

gorgeous slow movement. A nine-bar introduction creates

a nocturnal atmosphere with bell-like notes on flute and

harp over hushed strings. The cor anglais then sings the

plaintive first subject, immediately repeated and extended

by the soloist. After thirty-one bars it is taken up by the

clarinet, the soloist now accompanying with arpeggiated

chords across the strings. The second subject follows on

the strings with rising decorations by the soloist. The first

theme is repeated, now in F minor, with muted accom-

panying strings. A haunting romantic motif is heard on the

horns and will be heard several times before the end.

Eventually a cadenza-like passage of running semiquavers

presages the return of the cor anglais and a brief

orchestral climax before, musing on the horn’s romantic

motif, the music fades on the soloist’s long-held pianis-

simo top C.

The finale comes as a great surprise—a diaphanous

scherzando, all fairy gossamer. The music falls into a

succession of sixteen related short episodes. The first

theme starts in

and proceeds in

, its leaping triplet

motion giving it the feel of a saltarello. A contrasted theme in

appears in the strings in the fifth episode, and in the

next the first theme of the first movement returns in

staccato crochets. The writing for the soloist is brilliant

throughout, though d’Erlanger does not feel the need for

another cadenza.