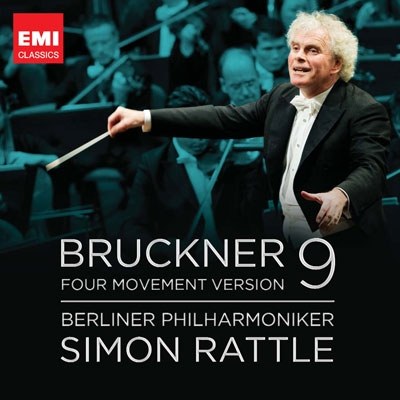

布鲁克纳:第9交响曲(4乐章版) 豆瓣

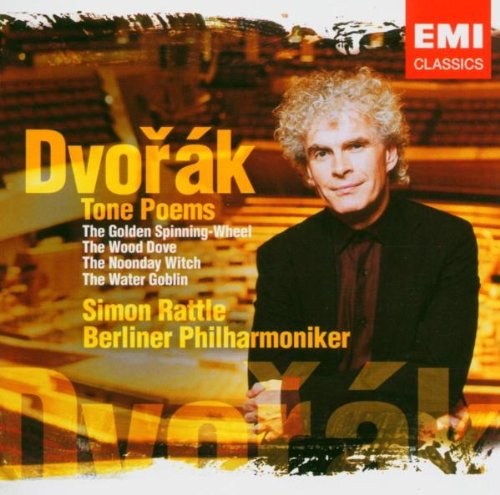

Sir Simon Rattle

/

Berliner Philharmoniker

类型:

古典

发布日期 2012年5月21日

出版发行:

EMI Classics

Sir Simon Rattle conducts the Berliner Philharmoniker in Anton Bruckner’s Symphony No. 9 including the world premiere of the latest scholarly revision of the fourth movement that the composer left unfinished at his death.

Sir Simon and the Orchestra unveiled the new version at Berlin’s Philharmonie in early February 2012 and at New York’s Carnegie Hall the same month. “It was fascinating to hear this monumental symphony performed with [its new] final movement. After a quizzical opening and a strong statement of the main theme there are stretches of fitful counterpoint, brass chorales and ruminative passages that take you by surprise. Overall the music pulses with a hard-wrought insistence that crests with a hallelujah coda.” (The New York Times)

On 11 October 1896, the day he died, Bruckner was still desperately trying to finish the final movement of his ninth symphony. He had completed and orchestrated one third of the movement and sketched the layout for the entire finale. Unfortunately, for scholars attempting to construct the remaining two thirds of the movement, many of the manuscript pages were subsequently stolen by autograph hunters. Some of these pages have resurfaced in recent years and several attempts have been made to complete the last movement, including four prior versions by the current musicological team of Nicola Samale, Giuseppe Mazzuca, John Phillips and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs.

“From a fresh re-examination of the manuscripts it was possible to find some convincing new solutions, binding the music even better together.” (Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs). With the benefit of 25 years of scholarship, this latest version is arguably the most comprehensive realisation of Bruckner’s sketches.

John Phillips adds, “The Finale is no musical curiosity, but an integral part of the work as its composer intended. Just as Beethoven designed his last symphony around its choral finale, Bruckner designed his Ninth around this huge, ultimately triumphant movement, synthesizing sonata form, fugue, and chorale. For the devoutly Catholic Bruckner, the symphony was to be his “homage to Divine majesty” […] The Adagio, his “Farewell to Life,” traces a gradual process of dissolution that leads us, spellbound, into the enigmatic music of the Finale [which] would end with a “song of praise to the dear Lord,” a “Hallelujah” borrowed from earlier in the work. And it is with this “Hallelujah” theme—the first entry of the trumpets in the Adagio—that the Ninth can so justly and so gloriously now conclude.”

In an interview for the Berlin Philharmonic's Digital Concert Hall, Sir Simon expressed his faith in the newly assembled four-movement version and begged audiences to be receptive to the new material. “There's a kind of myth that there are only sketches left of the last movement. In fact, there was really an emerging full score, complete almost to the end,” Rattle said, adding that Bruckner was writing in his most radical, forward-looking style in the Ninth, especially in the finale.

According to Gramophone, ‘to help listeners understand just how ‘complete’ the finale actually was at the time of Bruckner's death, Rattle compared the composer to an architect designing a cathedral. Indeed, Bruckner had the rather unique composition method of deciding how long his movements should be and then putting all the bars on the manuscript, numbered and with phrase lengths, even before writing the first note. “So actually, even when there are some empty pages, we know exactly how many bars there were and what kind of phrases there were,” concluded Rattle, explaining how much of the manuscript evidence was strewn throughout various collections. He also said that had the composer lived another two months, the finale would have been complete.’

For music lovers who discount the validity of any fourth movement to the Symphony No. 9, there is much to enjoy in the Berliner Philharmoniker’s performance of the first three movements: “Mr. Rattle and the Berlin players deftly balanced elements of Schubertian structure and Wagnerian turmoil in the mysterious first movement. The brutal power of the scherzo’s main theme was chilling, with the orchestra pummelling the dense, thick, dissonance-tinged chords. And Mr. Rattle laid out the threads of chromatic counterpoint in an organic, glowing and, when appropriate, gnashing account of the Adagio.” (The New York Times) For those with the intellectual curiosity to hear how accomplished Bruckner scholars have most recently realised the unfinished movement, it is performed here by the world-renowned team of Sir Simon Rattler and the Berliner Philharmoniker.

Sir Simon and the Orchestra unveiled the new version at Berlin’s Philharmonie in early February 2012 and at New York’s Carnegie Hall the same month. “It was fascinating to hear this monumental symphony performed with [its new] final movement. After a quizzical opening and a strong statement of the main theme there are stretches of fitful counterpoint, brass chorales and ruminative passages that take you by surprise. Overall the music pulses with a hard-wrought insistence that crests with a hallelujah coda.” (The New York Times)

On 11 October 1896, the day he died, Bruckner was still desperately trying to finish the final movement of his ninth symphony. He had completed and orchestrated one third of the movement and sketched the layout for the entire finale. Unfortunately, for scholars attempting to construct the remaining two thirds of the movement, many of the manuscript pages were subsequently stolen by autograph hunters. Some of these pages have resurfaced in recent years and several attempts have been made to complete the last movement, including four prior versions by the current musicological team of Nicola Samale, Giuseppe Mazzuca, John Phillips and Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs.

“From a fresh re-examination of the manuscripts it was possible to find some convincing new solutions, binding the music even better together.” (Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs). With the benefit of 25 years of scholarship, this latest version is arguably the most comprehensive realisation of Bruckner’s sketches.

John Phillips adds, “The Finale is no musical curiosity, but an integral part of the work as its composer intended. Just as Beethoven designed his last symphony around its choral finale, Bruckner designed his Ninth around this huge, ultimately triumphant movement, synthesizing sonata form, fugue, and chorale. For the devoutly Catholic Bruckner, the symphony was to be his “homage to Divine majesty” […] The Adagio, his “Farewell to Life,” traces a gradual process of dissolution that leads us, spellbound, into the enigmatic music of the Finale [which] would end with a “song of praise to the dear Lord,” a “Hallelujah” borrowed from earlier in the work. And it is with this “Hallelujah” theme—the first entry of the trumpets in the Adagio—that the Ninth can so justly and so gloriously now conclude.”

In an interview for the Berlin Philharmonic's Digital Concert Hall, Sir Simon expressed his faith in the newly assembled four-movement version and begged audiences to be receptive to the new material. “There's a kind of myth that there are only sketches left of the last movement. In fact, there was really an emerging full score, complete almost to the end,” Rattle said, adding that Bruckner was writing in his most radical, forward-looking style in the Ninth, especially in the finale.

According to Gramophone, ‘to help listeners understand just how ‘complete’ the finale actually was at the time of Bruckner's death, Rattle compared the composer to an architect designing a cathedral. Indeed, Bruckner had the rather unique composition method of deciding how long his movements should be and then putting all the bars on the manuscript, numbered and with phrase lengths, even before writing the first note. “So actually, even when there are some empty pages, we know exactly how many bars there were and what kind of phrases there were,” concluded Rattle, explaining how much of the manuscript evidence was strewn throughout various collections. He also said that had the composer lived another two months, the finale would have been complete.’

For music lovers who discount the validity of any fourth movement to the Symphony No. 9, there is much to enjoy in the Berliner Philharmoniker’s performance of the first three movements: “Mr. Rattle and the Berlin players deftly balanced elements of Schubertian structure and Wagnerian turmoil in the mysterious first movement. The brutal power of the scherzo’s main theme was chilling, with the orchestra pummelling the dense, thick, dissonance-tinged chords. And Mr. Rattle laid out the threads of chromatic counterpoint in an organic, glowing and, when appropriate, gnashing account of the Adagio.” (The New York Times) For those with the intellectual curiosity to hear how accomplished Bruckner scholars have most recently realised the unfinished movement, it is performed here by the world-renowned team of Sir Simon Rattler and the Berliner Philharmoniker.