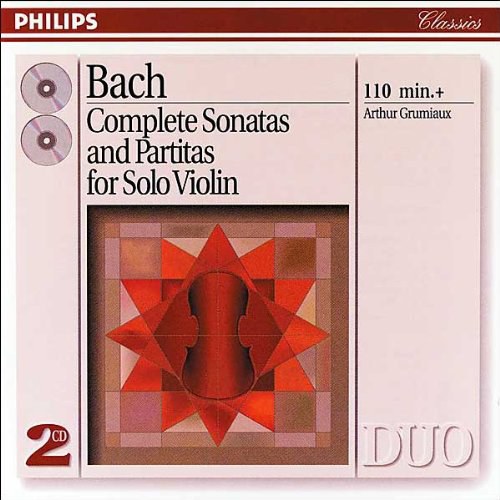

Bar code:

STEREO 289 457 701-2

0 28945 77012 3

--------------------------

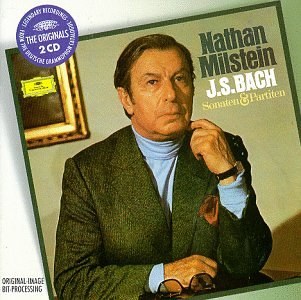

NATHAN MILSTEIN, Violine

Milstein on Recording Bach

“I just stopped making records about ten years ago. I don’t enjoy recording much; it makes me very nervous. When I play for a live audience I am nervous only until I get to the stage; once I’m on stage I feel like a fish in water. Recording does make me nervous, with the extra emphasis on perfection, but I do want to leave a record of my thoughts on the music that has meant most to me. I am not adding new material to my repertoire now; instead, I devote myself to the music I have lived with and loved for a half-century and more. I like the way my sessions are handled by Deutsche Grammophon. Where there is an error or some reason for a re-take, I won’t do a ‘surgical’ job, slipping in a note here or there: repairs must be co-ordinated so the emotional impact, the instinctive quality will be continuous, so the idea, the fire, the lyricism will not be interrupted by patches. If something has to be re-taken, I play a big part of it, for the sake of the continuity. I think the Bach Sonatas and Partitas I recorded for Deutsche Grammophon in London actually are clearly superior to the set I did in the ‘50s. There is nothing in my repertoire that I don’t play better now than I did before — simply because of the added experience I have now — and it is especially gratifying to be able to record these works under today’s technical conditions.”

The Bach solo works [...] have been Milstein specialties for years. [...] Bach, though, was something he had to discover on his own: “In Russia we didn’t have respect for Bach as a great composer. Of all his works, only a single fugue was included in our curriculum. In my Bach playing I stress the bass and the middle voices separately, with particular emphasis on the bass almost as a separate entity.” In Milstein’s definition, “virtuosity” has nothing to do with mere display, but indicates “the highest degree of professional excellence — in any sort of undertaking, not only a musical one. I think War and Peace is a virtuoso work.” He also distinguishes technique from mere dexterity: “technique is not just a matter of muscular control — technique means adjusting the medium to what I want to do.” The instrument Milstein plays is a 1716 Stradivarius he acquired in 1945, formerly known as the “ex Goldmann”. He has renamed it the “Maria Teresa”, in honor of his daughter Maria and his wife Teresa.

From a conversation with Nathan Milstein (1975)

Richard Freed

--------------------------

This is marvellous violin playing... Milstein’s special virtues are those of commanding technique: never is a note out of true in pitch or in rhythm.

Gramophone (1975)

... this is a magnificent set by any standard; from a performer close on 70 it is an achievement bordering on the miraculous.

Records and Recording (1975)

...this must surely rank as the seventy-year-old Odessa-born violinist’s crowning achievement. His interpretation, immaculately recorded by DG in a penetratingly clear yet warm ambiance, is so extraordinary that this three-disc album not only must be rated as one of this year’s finest releases but deserves to take its place among the greatest Bach recordings ever made. First, Milstein playing is impressive on purely technical grounds. So often these works tend to sound as though the performer is just barely going to make it through, especially in the contrapuntal convolutions of the sonatas’ three fugues; even at best, the rapid arpeggiation necessary to sustain three or four melodic lines all at once frequently results in an unpleasant scratchiness [...].

Technique aside, Milstein renditions have an unusually human quality. I find these to be warmly expressive readings in which the music is allowed to flow forward sensibly and the rhythms evoke all their dance origins. Slow movements, too, are handled in a wonderfully graceful manner. Finally, there is Milstein sense of pacing, which is something quite apart from his judicious choice of tempos. Rather it is revealed in a subtle rhetoric that causes a movement such as the Chaconne to build and grow from one climax to another. The pulse is always strong, the architecture always apparent, and the rubato-like inflections clarify the sentence structure of Bach’s phrases. Tonally, Milstein’s playing is quite beautiful.

Stereo Review (1976)

Every Phrase is shaped with meaning, every line is musically alive and in matters of technique there are no question marks either.

Gramophone (1976)

The Milstein set is the finest to have appeared in recent years. Every phrase is beautifully shaped and keenly alive; there is a highly developed feeling for line, and no want of virtuosity. ... Milstein is excellently served by the DG engineers, and the sound is natural and lifelike.

Penguin Guide (1977)

Milstein’s performances achieve both authority and spontaneity: the phrasing is supple, and the playing deeply felt without any suggestion of romantic indulgence. This is wholly admirable and can be recommended without reservation of any kind.

Gramophone (1977)

----------------------------

MILSTEIN PLAYS BACH

To understand the fascination that the solo Sonatas and Partitas of Bach had for Nathan Milstein, we first have to consider the works themselves. They were written in 1720, at a time when the composer was concentrating on instrumental music in his role as Kapellmeister to the court of Cöthen. As in so many other spheres, Bach did not invent a genre but improved immeasurably on the solo violin music written by some of his German contemporaries and predecessors. He was a good player of the violin and viola himself and in his Sonatas and Partitas he created abstract shapes and forms in which the player could seem almost to be communing with himself, yet still dazzle the audience. This is music in which the spiritual and virtuosic elements of the performance are so finely balanced that it is difficult to say where one ends and the other begins. Bach is not satisfied with a single line of music but throws in chords and even counterpoint, in which the harmonic drift of the music implies extra voices which are not actually present. The most amazing displays of this counterpoint come in the great fugues of the three Sonatas. The Partitas are at first glance simply suites of dances. Yet they demand many techniques which express the very soul of the violin — the exciting bariolage in the ebullient opening Preludio of the E major Partita, for instance; and the D minor Partita culminates in a Chaconne, a basically slow dance built on a repeated bass, which is perhaps the mightiest single movement the composer ever created. Here, using one small violin, Bach traces out one of his most amazing edifices in sound.

The 19th century did not really comprehend this music, and various attempts were made to fit piano accompaniments to the Sonatas and Partitas. Only with the emergence of Joseph Joachim did a major virtuoso grapple with the vast possibilities of these works; and by then problems had arisen through the steady evolution of the violin and the bow. Bach used a bow with a convex stick and his violin was strung across a flatter, shallower bridge, with tar less tension, because the neck of the violin was shorter and less angled. In the search for more volume, most of the old violins were modified to take a higher tension. The bow evolved into using a concave stick, which again allowed for greater tension. These factors made it harder to play Bach’s chords and most violinists of the early 20th century worked out compromises between Bach’s demands and their own capabilities. There were aberrations such as the Vega bow, a contraption by which the player could sound every note of a chord, even on a modern violin; but until the rise of the period instrument movement, playing Bach on the violin was a struggle. It is one of the imponderable paradoxes of music that although a number of “authentic” violinists have tackled the Sonatas and Partitas in recent years, their best efforts have not so far eclipsed the finest “compromise” players. Among the latter Nathan Milstein (1904-1992) held an honoured place. He brought to Bach the same instincts for style and taste that made him an outstanding interpreter of Mozart and Beethoven. In addition he had a technical facility and fluency second to none.

The surprising thing was that Milstein emerged from a milieu, the Russian bourgeoisie, in which Bach was not appreciated. Under his famous teachers, Pyotr Stolyarsky in Odessa and Leopold Auer in St. Petersburg, he played virtually no Bach, nor was he taught to understand the style. He eventually developed his own view of Bach through playing the marvellous solo violin works of Max Reger, in which Bach’s style was seen through the prism of a modern German intellect. Once Milstein came to the West in the mid1920s, he quickly assimilated what he needed to learn from his fellow fiddlers. Pre-war recordings show that by the end of the 1930s, he was already a nonpareil Bach violinist. He came to esteem Bach, alongside Paganini, as the finest writer for the violin — not that he equated the two composers in terms of quality — and he named the Chaconne as his favourite piece of music, sometimes programming it on its own. He recorded the Sonatas and Partitas in the 1 950s but felt that in this second cycle for Deutsche Grammophon he had said his last word on the music.

Milstein’s Bach is based on a secure sense of rhythm — vital for the slow movements as much as the fast ones. The dance movements really dance but always in an aristocratic way. Milstein’s tone, although of great beauty, never draws attention to itself through the overuse of vibrato. The listener’s attention is always focused on the musical line, because the player’s feeling for line and legato is so strong and his tone is so well focused. The big fugues and the Chaconne are spaciously laid out but urgently played, with such a comprehensive intellectual grip that the interest never flags. The same intellectual grasp ensures that Bach’s counterpoint is fully realized. The quieter, more inward moments are not italicized by romantic rallentandi. Instead Milstein relies on gradations of tone and volume and the tension of the musical line. Above all, these interpretations have the “size” of a great actor’s soliloquy: using no props other than his bow and his 1716 Stradivarius, Milstein comes before his audience with complete confidence that he can hold the stage. And because he is a musician of refinement and elevated ideals, the spiritual charge that should always inhabit Bach’s greatest music is present, alongside those equally characteristic outbursts of joy and exhilaration.

Tully Potter

--------------------------------

ADD

Produced by Werner Mayer

Tonmeister (Balance Engineer): Klaus Hiemann

Recording Engineers: Joachim Niss/Volker Martin

® 1975 Polydor International GmbH, Hamburg

© 1998 Deutsche Grammophon GmbH, Hamburg Cover &Artist Photo: Siegfried Lauterwasser

Art Direction: Hartmut Pfeiffer

--------------------------------

THE ORIGINALS

LEGENDARY RECORDINGS FROM THE DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON CATALOGUE

Deutsche Grammophon ORIGINALS — milestone recordings from our LP catalogue, now reproduced with unprecedented fidelity on CD. This new series of critically acclaimed performances features the great names of Deutsche Grammophon’s past and present: celebrated interpreters whose recording careers flourished at 33 rpm, as well as outstanding artists of today whose early achievements were documented on black vinyl. All recordings in the series have been newly refurbished using Deutsche Grammophon’s latest technology in order to “recreate” the original sound-image of these legendary interpretations.

ORIGINAL-IMAGE BIT-PROCESSING

To reproduce the original sound-image of a recorded performance as faithfully as possible: this has been the aim of Deutsche Grammophon Gesellschaft in developing its innovative digital mixdown technology ORIGINAL-IMAGE BIT-PROCESSING.

This technology, developed in conjunction with Deutsche Grammophon’s new 4D Audio Recording system at the company’s Recording Centre in Hanover, is based on the notion that the technical medium itself should become inaudible. It is only the means to an end, that of allowing the listener to enjoy an entirely natural sound quality.

ORIGINAL-IMAGE BIT-PROCESSING now makes it possible to remix older recordings in order to “recreate” the original sound- image. This recreation employs—wherever possible — physio-acoustical principles to compensate for delay factors (such as the time required for sounds to reach the main microphone) as well as an extremely high-resolution processing of the musical signals.

Authentic Bit Imaging, the requantizing procedure developed by Deutsche Grammophon, allows the extraordinarily high quality of this mixdown to be transferred optimally to digital sound carriers.

It is Deutsche Grammophon’s philosophy that technology alone is never sufficient. Optimal sound quality can only be achieved when technology is guided by the trained ear of an experienced Tonmeister Deutsche Grammophon’s Tonmeister combine technical expertise with a solid musical education.

For the listener to these performances, the audible results of this latest alliance of modern technology with traditional craftsmanship will be greater presence and brilliance and a more natural spatial balance than previously attainable.

-------------------------

WARNING! All rights reserved.

Unauthorized copying, reproduction, hiring, lending, public performance and broadcasting prohibited.

Manufactured and Marketed by PolyGram Classics & Jazz, a Division of PolyGram Records, Inc., New York, N.Y.

-------------------------

LP released 1975

Grammy 1975

Grand Premio del Disco “Ritmo” (Madrid) 1985

Recording: London, Conway Hall (Wembley, Brent Town Hall), 2, 4 & 9/1973